Being an appraiser is a combination of science, history, market research, and writing.

- katzdan3

- Aug 26, 2022

- 18 min read

Updated: Feb 2, 2023

Gina D’Onofrio

Master Gemologist Appraiser | Jewelry Appraisal Services

Where I began was Sydney, Australia in the mid-eighties, I was working in the jewelry industry selling opals. Then I started working part time for a retail jeweler who manufactured jewelry on site. He gave me an incentive to come and work for him full-time. He would pay for my gemology tuition, which was quite expensive. I didn’t really know what I was agreeing to at the time. But I guess it’s like anything, once you start learning something that really interests you, it takes you down a trajectory of discovery and I’ve been on that path ever since.

Up until 15 years ago, maybe 20, Australia was the largest producer of opals in the world, and then they found a new source in Ethiopia, East Africa. It’s a different kind of opal… Australia produces a couple of specific kinds of opals that are unique to Australia and Ethiopia has a very unique type of opal. When I was selling opals in Australia in a retail situation, I was in a historic arcade in downtown Sydney. We were selling opals, mostly to the tourist trade. The quality of what we were selling was more pedestrian, I guess; people wanted a memento, they didn’t want spend much money, but then there were always a couple of collectors that would come as well. Because the owner of the store had a passion for opals himself, he had his own private collection that was in the safe. So I did get to look at and play with some absolutely breathtaking specimens that I’m probably never going to see anything like again. I was exposed to really fine opals, but it’s not what we dealt in on a daily basis. They’re like little paintings, each one of them, and no two are the same.

When I studied gemology and I worked for that manufacturing jeweler, I also studied design, counter sketching, we created one-of-a-kind pieces for clients at that particular store. I also started appraising because it was an all-service jewelry store. It was a very small business, very hands on and we did everything. I moved on to another store in Sydney, which was one that specialized in antique and period jewelry and I got involved in buying jewelry from the public. So that was my exposure in Australia. When I left Australia and I lived in Canada for three years, I also worked in retail and for a manufacturer. I got involved in sorting diamonds and overseeing production of lines of jewelry. Then when I got here, a little bit of retail, mostly antique and period jewelry, little bit of watches, and then I went back into appraisals full-time and opened my own business in 2000.

In 2016, I took a break to work for an auction company. I was the jewelry director at the Beverly Hills office for Heritage Auctions and spent five years with them. It was a great experience and I worked with some amazing people but then it was time to come back to my business.

My gem lab is a little different to most appraisers' labs because of the advanced equipment I recently added. It was a huge investment but there is a serious need for gem testing at this level. I have a couple of spectrometers, what we call an FTIR and a Raman spectrometer. Also an EXA – photoluminescent spectrometer. They perform additional tests that standard gemological equipment cannot. The EXA screens for natural diamonds because now we have lab-grown diamonds. The XRF, a precious metals analyzer, tells me to the percentage how much gold, platinum, or other metal is in a piece. Whereas with the old-fashioned way, most of us use acids to test for purity. There are also newer electronic testers, but nothing as refined as the XRF. This rounds out a whole new suite of instruments that most appraisers don’t own.

Take the GemmoFTIR, for example: Somebody in the trade may bring to me a sapphire. It needs to be loose for me to really get a good reading. The FTIR can help me determine if the sapphire has been heat-treated. This supplements tests I make using standard equipment; I can already test and determine whether the stone is natural or synthetic. Under the microscope, I might get a pretty good idea of what country it might have originated from and whether a certain treatment has been applied to the sapphire. For example, 95% (give or take) of sapphires that come out of the earth have been subjected to heat treatment anywhere from 200, 400 degrees, all the way up to 1,500 degrees, sometimes higher. The reason why these sapphires are heated is either to drive out a purple component and make it more pure blue – there’s a chemical reaction going on with trace elements in the sapphire and it’s changing it – or it might be helping certain fine needles and inclusions in the sapphire dissipate so that the sapphire looks more crystal clean. You can improve color, you can take away color, there are all different things that you can do to improve a sapphire through heat treatment. But sapphires that come out of the ground that have not been subjected to heat – and are pretty – are very rare and sought after. That’s one value characteristic of the sapphire, aside from how pretty the color might be, how saturated the color is, how clean it is, how big it is, how well cut it is. These are all things that play into the value. Another element that’s playing into the value is what country it comes from. You may get a sapphire that is from Burma, Myanmar, or from Sri Lanka, they call them Ceylon sapphires. Knowing that origin combined with what’s been done to it, or not, is important to the value of the stone.

So this piece of equipment is another tool that helps me decide whether the sapphire may be from Ceylon and possibly un-heated. Essentially, I provide a screening service for people in the trade, or the public, before the stone is sent to the GIA, the Gemological Institute of America, which is an advanced lab here in California, or the AGL, the American Gemological Laboratory in New York, to get the final opinion. They choose to see me first in case I can save them time and money. Maybe it’s heat-treated and I’m pretty confident that it is, there’s no need spending another $800, $1,200, $1,500, depending on the stone, for the report to find that out. I can give them a verbal opinion and say, “You can stop there.” Or I might see that it’s potentially no heat, and then it is worth their while to invest the shipping, insurance and everything to get it to the lab and back, along with gem setting costs and lab fees.

My gem lab also includes the trusty microscope, ultraviolet light (short wave and long wave), the refractometer polariscope filters; there’s all kinds of instruments that I use to test gemstones to determine whether they’re natural, synthetic, or complete imitation. I have color grading equipment to measure the color and reproduce the color that I saw when the stone is no longer present. There’s a lot of equipment for weighing and grading diamonds. Millimeter gauges. I measure gemstones that are set in jewelry already so that I can calculate what they might weigh while they’re still sitting in a setting, because I can’t physically put them on a scale and weigh them.

Most of the trade were going, “Oh my God, no. What are we going to do? Synthetic diamonds.” I mean, they’ve been talking about it for years. What’s interesting is they’ve been growing diamond for decades. Decades! Since the late sixties, seventies. Most of them that came out of the labs were fancy colors. Highly saturated, too-good-to-be-true yellows and greenish yellows and orange. But up until 20 years ago, they weren’t able to produce truly colorless diamonds, and that over the last 20 years is something they have perfected. Twenty years ago, they were almost on a par with the cost of a natural diamond and as time has gone on with more people producing these stones, it has become a race to the bottom as far as the price goes. The good thing is yes, you can grow diamonds and it’s really exciting and technologically amazing. They are ethical in that they’re not funding terrorism. I question the opinion that they are sustainable because most diamond growers are using a lot of energy to produce these diamonds, so that’s up for debate but it’s providing a product to the public that is much more affordable than a natural mined diamond. Someone who maybe could only afford to buy a quarter carat stone in the past can now buy a one carat diamond for their partner, fiancé, whatever, so it’s making it more accessible. In that sense, I think lab-grown diamonds are great. The downside is they are a bad financial investment. Over the last three years, the value of somebody’s lab-grown diamond engagement ring has fallen. They may have spent a lot of money, but if they have to go out and buy it again today, I am watching the prices plummet. They are losing value over time because there are more and more lab-grown diamond producers so the market is becoming saturated.

The other downside to this is people are selling to dealers that buy pre-owned jewelry, and they’re not disclosing that what they’re selling are manmade diamonds. Or maybe they don’t know? These stones are being circulated back into the trade, then presented to the public as a natural diamonds because the seller doesn’t know what they have, or they haven’t spent the money to find out. Another downside is there’s a lot of jewelry that is manufactured abroad in developing countries where the people who are setting diamonds in the jewelry, working for pennies each day, are tempted to mix in with the natural diamonds a few lab-grown diamonds here and there. Imagine a piece that has lots of small diamonds. It is possible that some of it will be lab-grown because of this diamond setter who succumbed to temptation. The manufacturer is unaware so it wasn’t disclosed to the retail buyer. There’s good and bad to it. I see these manmade diamonds on a regular basis because my younger clients buy them for engagement rings. They still need to insure them so I get to play with them, test and grade them. They are beautiful diamonds. It’s a complicated situation.

There’s two main processes. One is high pressure, high temperature – HPHT, they call it – and that was the more traditional version. They would start out with a seed plate and then it’s mostly carbon ingredients. Under high pressure, high temperature they would crystallize this material; they would mimic what was happening in the earth. The newer method, which is called CVD or chemical vapor deposition, is basically carbon atoms in a vapor being deposited onto a diamond seed plate where it crystallizes. It takes a few weeks. And that method is producing chemically pure lab-grown diamonds. The need for lab-grown diamonds in technology is far greater than in the jewelry industry; the jewelry industry is just a small iota of where they plan to use these lab-grown diamonds. It’s really going to be exciting to see how this new technology is applied to optics and medical equipment. They’re even thinking maybe down the road, there might be a diamond computer chip because they’re so optically and chemically pure.

But what people may not remember or be aware of is they’ve been growing rubies and sapphires for a hundred years now. Lab-grown sapphires came on the market in the early 20th century and rubies a bit earlier. They’ve been growing synthetic emeralds for about 70 years. Then came lab-grown opals. Very impressive ones! Also alexandrite, all kinds of stones. They’ve been able to mimic what nature does and grow them in labs and they’re out there in the marketplace. Just like manmade diamonds, they were very expensive to start with then the price fell as technology improved and more growers come on the market.

The technique for producing them is a lot easier than the technique for producing diamonds. For example, they would start off with the chemical makeup of what makes a sapphire, aluminum oxide, and then they would melt it at a very high temperature, and then they would let it drip onto a surface where it would crystallize as it cools. They’d end up with these tubes (called boules) of manmade sapphire and ruby and then they would facet it. That was just one method. There’s a few that they used, but that was the earlier method. What we look for as gemologists are signs of that cooling and crystallizing, or signs of unmelted aluminum oxide, which we call unmelted nutrients. Often gas bubbles form: when it drips and cools, that’s a dead giveaway because you don’t get gas bubbles in natural rubies and sapphires. We also see these little curved growth lines the stone that don’t exist in nature. It’s a result of the cooling onto a rounded surface.

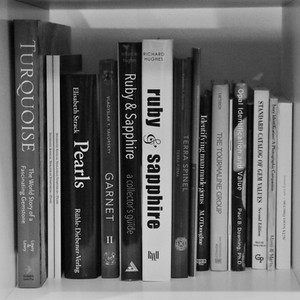

I could geek out about this stuff, the interior of manmade and natural gemstones. We have books here in the trade that are reference books of photomicrographs of gemstone inclusions. This shows the interior of an emerald from Tanzania, typical inclusions, growth structures and why they’re there. This little blocky type of inclusion with a bubble inside… you know how I said gas bubbles don’t occur? But when you have a bubble inside what we call a negative crystal, that’s natural and this is typical of an emerald from Pakistan or Mozambique. So the whole inclusion scene tells me about what a gemstone is and where it came from. In the jewelry industry, people are saying, “Diamonds, diamonds, diamonds, aren’t diamonds wonderful?” but the most fascinating part of it to many gemologists are the color gemstones and what’s going on inside them.

For some reason, jewelry appraisers are not licensed. Anyone can put a sign on the door declaring they’re a jewelry appraiser, with absolutely no training. No one will stop you and no one will hold you accountable….unless you get sued. There are people in the trade who buy and sell jewelry – they’re merchants. Often, not even gemologists, yet they are appraising jewelry. They can get away with it up to a certain point but, one day, they’re going to appraise something and it’s going to be so incorrect that it will cause financial harm to their client, landing them in court where they will lose their shirt. I’ve been on the other end of this scenario as the expert witness in a situation where a collection of jewelry was sold to a client and appraised incorrectly. They lost the case and the store closed down. I didn’t know what happened until after the fact; I was just asked to appraise the collection. There’s no regulation. Appraisers choose to self-regulate in this industry by taking exams and becoming accredited with a respected appraisal organization. Sadly, there are very few of us.

Most of the people out there that are writing appraisal reports do not have any formal training. Some insurance companies are starting to request that the appraiser is certified, but even then, they don’t know what they’re requesting. For example, when the consumer asks, “Are you a GG?” the ‘appraiser’ will say yes because they studied gemology at the GIA, but they have zero other training. No appraisal report methodology, no jewelry history, manufacturing, no nothing. Just step one. Yet, that person meets the criteria that the insurance company asked for.

There are other reasons why consumers need appraisal reports, insurance coverage is just one aspect. For example, if somebody passes away and the estate is taxable. The IRS requires that an estate that exceeds a certain value must pay estate taxes. Appraisers need to appraise the jewelry that is taxable. I understand the value definition, the methodology that the IRS requires, because I’ve done the training and I do all the proper market research and report writing to support my value. But if you don’t have training in this type of appraisal, you might do an appraisal report for replacement value, as you would for an insurance appraisal. If the jewelry is vintage, in used condition, it’s only available in the secondary market – that should be the market that’s being researched. The piece could be over-appraised at a much higher value than what it truly is in the marketplace. The estate is paying taxes on that, so they’re losing money because it wasn’t properly appraised. So there’s all kinds of reasons why the training is important. On the other hand, if the piece is under-appraised, resulting in lower taxes as a result, it is quite possible the IRS flag it for review. What if the piece is unique and offered for auction at a later date and it sells for maybe 20 times what it was valued at? The IRS can go after the estate for back taxes, fine them; then go after the appraiser and fine them, too.

Being an appraiser is a combination of science, history, market research, and writing. I might do an enormous amount of market research on something that’s complex, difficult to price. Sometimes I get caught up in the research; I find it hard to stop even when I have enough info to form an opinion with. I love the research but it just gets to the point where I’m I working for minimum wage. Sometimes there are limitations, information that is incomplete. At some point I have to make a choice, base my value on that choice and explain why I did what I did clearly in the report. Sometimes, even after the report is delivered, I’m still second guessing myself, because a certain amount of it is open to interpretation or based on what information was available to me at that time. The appraisal report is finished. It’s signed, sealed, delivered. It’s out there. Decisions are being made based on my work. There’s all kinds of ifs and buts that I have to explain in the appraisal. The second-guessing is because we sometimes have to form an opinion based on something that we can’t see completely. For example, I could be grading a flawless diamond, but it’s inside a platinum setting and parts of that diamond are concealed by prongs. Try as I might to get it as clean as a whistle and look at it under high magnification, look under the prongs from every angle... I still can’t see the whole diamond. But from what I can see, it looks flawless. But it’s potentially not flawless. I have to arrive at an opinion. I give it my best shot and I say, I think it’s not flawless. I think it’s the next step down. Or I think it’s flawless just based on what I can actually see. There’s the “but” right next to the price where I explain it all.

Despite all of the effort, when I deliver an appraisal report to a client, nine times out of 10, they don’t read the report. They flip to the page that has the value and then they’re done reading. That’s all they care about. Maybe they’ll check the grade, color, clarity. And that’s it! All the ifs and buts are completely overlooked. Yet, they’re important for so many reasons. I try and explain it to clients when they’re with me, if they’re sitting with me while I do the grading. A diamond, flawless, that’s an easy thing to explain, but then you’re talking about this piece of equipment to determine whether it’s no heat, if it’s from Ceylon. The value from no heat to heated is enormous. The value of a sapphire coming from one region or another is enormous. It can be double, it can be triple, and sometimes even more. There’s a lot of ifs and buts you have to explain, but if the client is not willing to go the extra expense to have the stone removed for further testing, I’m still expected to arrive at an opinion then report what I did. Most of the time, I feel really good about my decision but, there’s always that 1% in the background that nags, “Yeah, but what if… what did I miss? What are they not telling me?” Still, that keeps it interesting. I like the challenge.

It’s all exposure, you learn, gain expertise in what you’re exposed to. I try and see as much as possible. Professional appraisers happily travel to trade shows, different stores, antique fairs, conferences so that we can see and learn as much as possible. That’s how we all develop our connoisseurship, how we develop our ‘eye’. We also have to have an understanding of how jewelry is made. Not just the gemstones and diamonds, but what it takes to produce a jewel. There are many different ways to make the same piece. Figure out how it was made and that will inform you as to how much time went into making it, how much expertise, how old the piece may be. The jewelry is going to tell you that. Then there are the stamps, signature, numbers, maker’s marks that you have to have an understanding of. That’s another area of study.

I will have a client who might be the trustee of an estate, who might also be the family member of the deceased and they will bring the entire jewelry collection from this person that recently passed away. They don’t realize it until they bring it here that the jewelry is actually telling me the story of this person’s life. It’s telling me what their humble beginnings may have been, or it’s telling me where they lived. Because quite often, jewelry has different country marks or assay marks, or it tells me where they’ve traveled. Jewelry can be very sentimental. It’s speaking to me in that sense. It’s telling me what their style was at different eras when they were actively buying. It’s also telling me a little bit more about their taste as well, what their personality was like. I’m looking at this jewelry and I’m analyzing it and I’m testing it. Clients often sit with me while I do the evaluation while I’m doing the testing and grading and note taking and photography and taking down all the important information about the piece. I tell them as I go along what I’m seeing, and I’ll tell them, “This piece is French and it looks like it was probably made in the 1930s, maybe just before World War II,” and then suddenly they’ll say, “Yes, that’s right! My great-grandmother went to Paris for a short period of time in the late 1930s and she was displaced just before the war and then they moved to New York…” It coincides with the jewelry because from 1940 on, I can see that the jewelry is no longer manufactured in Paris or anywhere else in Europe, it is American, signed by American makers or there is a certain look about a piece that tells me that it’s from the U.S. It’s like a jigsaw puzzle. I say a little, they tell me a little, and we are piecing together this person’s life story just from the jewelry collection. And quite often the most interesting piece is the least valuable, but the most significant for one reason or another. It’s wonderful to be able to share that with someone who the person was so important to, and then they can pass that information on to the rest of the family.

Jewelry and gemology, it’s a subject that you can keep working on for the rest of your life and still just scratch the surface. For all those people out there in the industry who think that they know it all… don’t believe it, not for a second. We’re all eternal students and we all have our little area of specialty where we tend to focus but everybody doesn’t know everything. That’s why we share our knowledge and consult with other experts that we trust.

The last 15 years of my career, I’ve been more involved in education. I was active with the American Society of Appraisers; I was their education chair, which involved developing education and finding educators to cover subjects our appraisers might need to know. I got involved in teaching appraisal theory and report writing. Also, for many years, up until COVID hit, served as a mentor at the GIA career fair. Students would make appointments to speak with me, to learn about what I do and what it takes to get to where I am and how does one become an appraiser.

With this experience, and also through my own learning journey, I became painfully aware of all the holes in appraisal education and how hard it is to acquire the information that we have acquired. Those of us that have been in the industry for decades now, know how long it took for us to learn what we learned. And even then, there’s really no formal path for us to get that education. It’s all piecemeal. You get your diploma in gemology. You learn how to identify gemstones and grade diamonds, but that’s just your first baby step. There’s just so much out there and unfortunately, when you’re just getting started in this industry and you’re studying gemology, you don’t know what you don’t know. It’s stunning what people don’t realize they need to learn and can go through a whole lifetime in the industry and not learn it. It would have been very valuable to them had they known. Or they could have been so much better at what they did had they known. So, I’ve been trying to plug the holes.

I felt that there was a desperate need for appraisers and people in the industry who did not know how to make jewelry but needed to have an understanding of how jewelry was made so that they could properly evaluate it and appraise it and identify it. We needed a course for this yet there wasn’t one. I asked GIA if they would be willing to develop one for ASA and they did! They agreed to offer it to ASA for a year. It was just a short course, it was a day and a half. I was actively consulting with them to help them to provide the appraiser’s perspective and what info would be helpful to us. They named it Jewelry Forensics and it has evolved over years. Now it is a course that GIA is offering online and on campus. It was something I started, but I’m no longer involved in it. It was produced out of a need for information. As more and more people learn that this information is out there, more and more people will benefit from it.

Over the last five years, I’ve been focused on an understanding of more recent jewelry history because there’s plenty of attention on Art Deco, Victorian, Georgian, Edwardian jewelry from 150 to 200 years ago, right up to about a hundred years ago. But these days, 80% of the jewelry that most appraisers are looking at was produced from 1950 on. There’s no formal education on circa dating and understanding the designs and why the designs occurred… more like art history for jewelers. So I launched into a lot of study and I developed lectures by the decade and then offered them in two-decade blocks, like jewelry of the forties and fifties. Jewelry of the sixties and seventies, jewelry of the eighties and nineties. I also did it as a one-day course for all five decades. Even my peers, who lived and worked through those decades, have gained a new perspective. I’m often approached by young gemologists or gemology students at GIA who are saying, “I want to be an appraiser,” but they don’t know any jewelry history. They don’t know anything about how jewelry is manufactured. So how are they going to appraise it? There’s valuable information on more recent jewelry history that I’m working on in these courses, and I also plan to put it into a reference manual.

This information is also important to a consumer so that they know what they’re buying. Not just to know, but appreciate it and understand and enjoy that piece even more because they know how extraordinary it is or what caused that design to evolve or what made that designer of that period so collectible and so special. Once they understand that, then they’ll have a much bigger appreciation for the piece of jewelry that they have. They can pass that information on and they can become better collectors.

Nobody knows everything. With evolving research and technology, this information is constantly in a state of flux It’s a big subject. I’m well into my fifties, so I might have a good 10, 15 years of full-time work left in me. After that I might want to start winding down a little, and I feel that this is the time where I have to start giving back to the trade, giving back to the industry, and also try and solidify everything I’ve learned and put it into a more accessible package for people coming up behind me to learn.

Comments